Introduction

As part of the Series of Webinars on Islamic Studies, the Misbah Institute, in collaboration with the Research Institute for Islamic Culture and Thought, organized a session entitled “The Trajectory of Islamic Studies in North American and European Universities over the Past 25 Years.” The webinar was held on Wednesday, July 23, 2025, with Professor Liyakat Takim  as the keynote speaker and Dr. Morteza Karimi serving as the academic moderator.

as the keynote speaker and Dr. Morteza Karimi serving as the academic moderator.

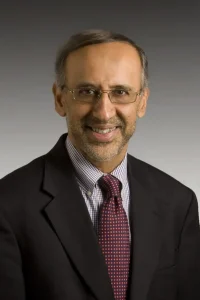

Professor Liyakat Takim, originally from Zanzibar, Tanzania, is the Sharjah Chair in Global Islam at McMaster University, Canada. A prolific scholar and public intellectual, he has authored and translated eight books, with his ninth forthcoming on Qurʾānic exegesis. His most recent monograph, Shiʿism Revisited: Ijtihād and Reformation in Contemporary Times (Oxford University Press, 2022), explores pressing debates on reform within Shīʿī thought. Beyond his books, Professor Takim has published over 140 scholarly works in journals, edited volumes, and encyclopedias, and has spoken at more than 120 academic conferences worldwide.

His research spans a wide range of themes, including reform in Islam, Qurʾānic exegesis, the role of custom in shaping Islamic law, Islam in the Western diaspora, Islamic fundamentalism, Sufi traditions, Islamophobia, and the treatment of women in Islamic law. He has also made significant contributions to the study of Shīʿī Islam in North America, with works such as Shiʿism in America (New York University Press, 2009) and The Heirs of the Prophet (State University of New York, 2006). In addition to his scholarship, Professor Takim is deeply engaged in interfaith dialogue and teaching across diverse academic settings.

The Establishment of the Sharjah Chair in Global Islam

At the outset of his lecture, Professor Takim provided a brief account of the origins of the Sharjah Chair in Global Islam at McMaster University. The position was established in 2008 when the president of McMaster University, through direct contact with the Amir of Sharjah, secured an endowment to create a chair dedicated to the study of global Islam. Following the endowment, the university announced the position, and Professor Takim was subsequently appointed.

He assumed the role in 2009, and as of 2025, he has served in this capacity for seventeen years. The title Sharjah Chair is directly linked to the Amir’s generous contribution, which enabled the creation of the post. Professor Takim also recalled his personal meeting with the Amir of Sharjah, during which they discussed the significance of the position and its objectives at McMaster University.

The Historical Roots of Western Hostility Toward Islam

In framing the trajectory of Islamic studies in the West, Professor Takim emphasized the importance of historical context. He argued that contemporary dynamics, including the phenomenon of Islamophobia, cannot be fully understood without reference to the past. The arrival of Islam in Europe was perceived as a profound challenge, particularly in Western Europe, where it was viewed not merely as a political rival but as a theological threat. Core Christian doctrines such as the Trinity and the resurrection of Jesus were directly contested by Islamic teachings, which led to a perception of Islam as an existential challenge to Christian orthodoxy.

This sense of threat was not confined to abstract theology but extended to attacks on the very person of the Prophet Muḥammad. Professor Takim pointed out that what is today labeled “Islamophobia” is, in fact, a continuation of a long-standing discourse of hostility. He cited the example of John of Damascus (d. ca. 749), who, despite living under the Umayyads in Damascus, wrote extensively against Islam and the Prophet in highly derogatory terms. Such polemics established a pattern of demeaning representations of Islam and its founder that persisted for centuries, both in popular culture and in early scholarly writings.

By situating Islamophobia within this long history, Professor Takim highlighted that modern antagonisms are not novel inventions but part of a deeply rooted tradition of opposition.

Early Translations and Polemical Representations of Islam

To illustrate the persistence of anti-Islamic sentiment in the West, Professor Takim drew attention to early European translations of the Qurʾān. The first known Latin translation, completed in 1143 by Robert of Ketton under the patronage of Peter the Venerable, was not undertaken with the purpose of understanding Islam on its own terms. Rather, its objective was polemical: to identify perceived faults in the text and to provide a theological arsenal for Christian critiques of Islam. Such projects reflect how translation itself was embedded in a broader agenda of opposition.

terms. Rather, its objective was polemical: to identify perceived faults in the text and to provide a theological arsenal for Christian critiques of Islam. Such projects reflect how translation itself was embedded in a broader agenda of opposition.

This hostility also manifested in language and terminology. For example, the medieval term mammetry—derived from the name of the Prophet Muḥammad—was used to denote “idolatry.” The implication was that Muslims were idolaters who worshipped Muḥammad, a claim entirely at odds with Islamic monotheism. Yet the very existence of such terminology demonstrates how deeply anti-Islamic narratives shaped European discourse.

Professor Takim further noted how this tradition extended into European literature. Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, one of the canonical texts of medieval Christendom, relegates the Prophet Muḥammad and Imām ʿAlī to the lowest circles of hell. Such depictions not only reinforced existing prejudices but also enshrined them within the cultural and literary canon of Europe.

By highlighting these examples, Professor Takim underscored how translation, language, and literature all functioned historically as instruments for distorting and denigrating Islam.

The Emergence of Orientalism in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

Professor Takim situated the development of Orientalism within the broader intellectual climate of early modern Europe. From the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Orientalism emerged as the Western study of the “Orient,” constructed through European assumptions and frameworks rather than indigenous perspectives. Often, these studies relied on isolated case analyses or even mere conjectures, which were then generalized to represent the entire Islamic world. In this way, the “Orient” became less a reflection of lived realities than a projection of European cultural and religious anxieties.

Sunni-Centric Frameworks and Limited Access to Shīʿī Sources

A critical point underscored by Professor Takim was that much of Orientalist scholarship focused on Islam primarily through a Sunni lens. Shīʿī Islam was rarely studied in its own right, and when it was, the Fatimid experience served as the dominant interpretive framework. This was due in part to limited European access to Shīʿī sources. European travelers provided anecdotal accounts of Shīʿī practices, but such observations lacked the depth of rigorous scholarly engagement and often reinforced stereotypes rather than offering nuanced insights.

Shifts in Orientalist Scholarship since the 1960s

The trajectory of Islamic studies began to change markedly in the 1960s. With greater access to Muslim-majority societies and the entry of Muslim scholars into Western academia, more balanced and rigorous studies of Islam—including Shīʿī Islam—began to emerge. Scholars such as Louis Massignon and Henry Corbin played pivotal roles in bringing Shīʿī philosophy and thought into academic discussions, with Corbin in particular studying under ʿAllāma Ṭabāṭabā’ī in Iran.

This period also saw the arrival of prominent Muslim and Shīʿī scholars in Western academic institutions, including Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Hamid Algar, Mahmoud Ayoub, and Abdulaziz Sachedina. Professor Takim himself entered academia as a graduate student in 1981, part of a wave of Shīʿī scholars who contributed to reshaping the field.

The Impact of the Iranian Revolution and Political Developments

Another major turning point was the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the subsequent rise of movements such as Hezbollah. These events significantly heightened global interest in Shīʿī Islam. Whereas earlier scholarship tended to subsume Shiʿism under broader studies of Islam, after 1979 scholars increasingly asked: Who are the Shiʿa? What do they believe? What distinguishes their rituals and practices? The Revolution, alongside the intellectual contributions of Muslim scholars within the academy, thus catalyzed a greater scholarly engagement with Shīʿī thought, identity, and practice.

Developments in Islamic Studies since the Year 2000

A. Increasing Presence of Muslim Scholars in Academia

Since the early 2000s, the presence of Muslim scholars within Western academia has grown significantly. Professor Takim recalled his own experience in the 1990s, when panels on Islam at the American Academy of Religion (AAR) annual meetings were limited to one or two sessions among thousands of presentations. By contrast, in recent decades Islamic studies have expanded into multiple specialized subfields—such as Qurʾānic studies, Sufism, Shiʿism, and Islam in modern contexts—reflecting heightened scholarly and institutional interest. Parallel to this development, a substantial body of publications has emerged on diverse themes ranging from Shīʿī ritual practices in India to contemporary political and social dynamics in Iran.

B. The Emergence of More Rigorous Methodologies

Another major shift has been methodological. Whereas Islamic studies in Western universities were historically conducted primarily by non-Muslim scholars—often Christians, Jews, or Bahá’ís—today an estimated 60–70% of faculty members teaching Islam in North America are Muslims themselves. This insider presence has encouraged more nuanced perspectives while retaining the academic requirement of objectivity. The distinction between confessional and academic approaches remains crucial: while scholars may personally adhere to Islam, their analysis must employ critical, historical, and sociological methodologies rather than devotional frameworks.

C. The Transformative Impact of September 11, 2001

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, proved to be a watershed moment in the study of Islam. Public curiosity about Islam surged, leading to a rapid increase in university courses, research projects, and faculty positions. Qurʾān sales spiked, and universities that previously offered limited courses on Islam began developing entire programs. Professor Takim himself noted that his first day of teaching a course on Islam at the University of Denver coincided with September 11, 2001—a symbolic convergence that underscored the urgency of academic engagement with Islam in a rapidly shifting global climate.

D. The Phenomenological Approach and Methodological Innovations

Since 2000, greater emphasis has been placed on phenomenological and interdisciplinary approaches. Phenomenology here refers to the study of Islam as a lived religious phenomenon, examining how Muslims themselves experience and articulate their faith. This approach remains distinct from confessional commitments: Muslim scholars are encouraged to retain personal belief while simultaneously applying rigorous critical methods.

Methodological diversity has also expanded. Historical and chronological approaches trace the evolution of Islamic doctrines over time. Sociological frameworks, such as Max Weber’s theories of charisma and authority, have been applied to classical Islamic concepts, as in Professor Takim’s own work The Heirs of the Prophet. Similarly, scholars borrow from Western theories of ritual and religion (e.g., Victor Turner, Catherine Bell, Rudolf Otto) to analyze Islamic practices such as ʿAzādārī and prayer. Such methods, rarely taught in traditional seminaries (ḥawzahs), have become standard components of graduate training in religious studies in North America.

E. The Role of Shīʿī Scholars and Institutional Challenges

While Shīʿī Islam has gained increasing attention in Western academia, the number of Shīʿī scholars remains limited. Professor Takim emphasized that only about 25–30 Shīʿī professors are currently active in North America and Europe, with many senior figures—such as Mahmoud Ayoub, Abdulaziz Sachedina, Hamid Algar, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr—either retired or deceased. He called for greater efforts to train new Shīʿī scholars and to establish endowed chairs in Shīʿī studies, noting that relatively modest financial investments could have long-lasting academic impact. Unlike other traditions, Shiʿism has not yet institutionalized a significant presence through endowed chairs, apart from isolated cases such as the Imām ʿAlī Chair in Hartford Seminary.

F. Emerging Approaches: Textual Hermeneutics and Ritual Studies

Finally, recent years have witnessed the introduction of new approaches to the interpretation of Islamic texts and rituals. Hermeneutics, the study of interpretive frameworks, has become increasingly central. Tafsīr literature, for instance, demonstrates that exegetical methods and emphases shift across generations—from Qummī and ʿAyyāshī, to Ṭūsī and Ṭabrisī, to later scholars such as Fayḍ Kāshānī, ʿAllāma Baḥrānī, and ʿAllāma Ṭabāṭabā’ī. Each reflects not only theological commitments but also the intellectual climate of its era.

In parallel, ritual studies have gained prominence, with scholars applying sociological and anthropological theories to practices such as Muḥarram commemorations. This reflects a broader academic trend of examining religion not solely as a set of doctrines but also as embodied and enacted practices.

The Contribution of Muslim Scholars in Western Academia

One of the questions raised concerns the extent to which Western academia has benefited from the contributions of Muslim scholars living outside the West. In Professor Takim’s view, a serious scholar of Islam must be familiar with both Eastern and Western traditions of learning. This is because certain subjects are taught in the ḥawzah that are absent in Western universities, and conversely, many subjects that are central to the academic study of Islam in the West are not taught in the ḥawzah. Thus, collaboration between the two spheres is essential.

For instance, Western universities have benefited enormously from studies in uṣūl al-fiqh—a discipline not typically taught in Western academic settings. Some scholars, both Western and Eastern, have written about it, allowing us to incorporate those insights into the broader study of Islam. One prominent scholar is Robert Gleave, based in England, who has contributed significantly to Shīʿī studies and uṣūl al-fiqh. Ironically, until quite recently, more non-Shīʿī scholars wrote on Shīʿism than Shīʿīs themselves. Names such as Etan Kohlberg, a Jewish scholar, stand out for their extensive work on Shīʿī Islam. Similarly, Norman Calder—who happened to be one of his examiners when Professor Takim defended his thesis in London in 1990—produced highly valuable contributions to the study of Islamic law.

At the same time, there are subjects taught in the West which are not covered in the East, such as critical studies, methodological approaches, Islam in North America, Islam in modern times, Islamic mysticism, and especially gender studies. While discussions on women in Islam exist in the ḥawzah, to his knowledge, a structured course on gender studies as a distinct academic discipline is still lacking there. Although Qom has changed significantly since Professor Takim’s own time there in the 1980s, much could be gained through greater collaboration.

What Muslim Scholars in the East Can Learn from the West

The question also arises: what can Muslim scholars in the East learn from developments in Islamic studies in the West? According to Professor Takim, one area is comparative religion. For years he taught courses in Denver on Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Unfortunately, many Muslim students hesitated to take these courses out of fear that their faith might be weakened. But he always tells them: if a student studies Judaism or Christianity and then abandons Islam, the problem lies not in Islam but in the weakness of their faith. A strong faith enables us to learn from others, benefit from their insights, and still remain confident in our tradition.

Another crucial area is the study of the theories and development of Islamic law. This is not merely the study of fiqh rulings but the intellectual and historical processes by which Islamic law has evolved over centuries. For example, the writings of Shaykh Ṭūsī differ substantially from those of contemporary authorities such as Ayatollah Sistani or Ayatollah Khamenei. Understanding how these ideas developed comparatively—between Sunnī and Shīʿī traditions—is a key part of the courses Professor Takim has taught.

Scholars like Norman Calder, although not Muslim, offered valuable structural and methodological insights into the study of Islamic law and texts. Such theoretical frameworks can also be fruitfully applied to the Qurʾān and tafsīr, as he is doing in his current research.

Advice to Young Muslim Scholars

Professor Takim remarked:

My advice is very simple: do it. I strongly encourage young scholars—especially from Iran—to enter the academic study of Islam. I myself have supervised several Iranian doctoral students, some of whom now teach in the West and others in Iran. Political restrictions unfortunately prevent Iranian scholars from teaching in the United States, but opportunities exist in Europe and elsewhere.

What is important is that Muslims themselves should teach Islam in the academy, rather than allowing it to be taught exclusively by others. To succeed, however, requires more than good intentions. Young scholars must acquire the necessary tools—methodological, linguistic, and theoretical—to study Islam critically and academically.

One of the courses I currently teach is called What is Islam? (formerly titled Introduction to Islam). Attracting up to 100 students, many of whom are not specialists in Islamic studies, it goes beyond simple description. We examine Islam through the lenses of law, philosophy, mysticism, and ritual practice. For many students—whether they are studying engineering, medicine, or law—this may be their first sustained encounter with Islam. If we, as Muslim scholars, can shape their understanding, we indirectly influence the broader perceptions of Islam in society.

To young scholars, I would emphasize two things above all: breadth and depth. Acquire a broad exposure to different fields, but in each field, go beyond surface description to genuine analysis. And always combine study in the ḥawzah with academic training in the West. A serious Shīʿī scholar must master both Arabic and Persian, and must be equipped with the tools of both traditions in order to contribute meaningfully to global Islamic studies.

Emerging Fields in Islamic Studies

Are there new fields being introduced into Islamic studies? The answer is yes—areas that have been largely unexplored in the ḥawzah but are now beginning to be developed in Western academia. For example, one of Professor Takim’s current students is completing a dissertation on Islamic environmental ethics—a subject of growing importance but not yet formally taught in traditional seminaries.

Other emerging areas include:

- Gender studies in Islam, where some scholars are now teaching specialized courses on gender theory and Islam.

- Biomedical ethics, which addresses pressing issues of medical practice, technology, and Islamic law.

- Pastoral care and counseling, particularly for Muslim communities in Western contexts.

These fields represent directions in which Islamic scholarship can expand, making it more relevant to contemporary challenges.

Differences Between European and North American Approaches

There are also important differences between how Islamic studies are structured in Europe and in North America.

In Europe, doctoral programs are often more straightforward: once a research proposal is accepted, a PhD student can begin writing immediately without the requirement of coursework. Institutions such as Exeter, SOAS in London, or Durham follow this model.

In North America, by contrast, students typically spend the first two years completing coursework. At first, this may seem burdensome, but in reality, it is an advantage. Coursework provides students with a wider range of tools, perspectives, and subjects they can later teach. Comprehensive examinations are also required in North America, whereas they are generally absent in European programs.

This difference also shapes employability. In North America, when a university advertises a faculty position, it is often not limited to Islamic studies alone. Candidates may be expected to teach in related areas, such as theories of religion, comparative religion, or Judaism. Professor Takim added:

“Personally, I was not formally trained in all of these areas and had to prepare myself, but the system of coursework and comprehensive exams helps future scholars to be more versatile. To give a recent example: one of my Iranian PhD students just completed his comprehensive exams last week and is now beginning to write a dissertation on artificial intelligence (AI) and the ḥawzah—an area that illustrates how even cutting-edge fields like AI are now entering into Islamic studies.”

Q&A Session

At the end of the webinar, Professor Liyakat Takim responded to a series of questions from the audience. Below are some of the most significant questions and answers.

Question 1:

You mentioned that since the year 2000, more Muslim scholars have become involved in the field of Islamic studies compared to earlier decades. My question is: has this development been welcomed by non-Muslim scholars, or has it been met with resistance?

Answer:

Overall, I believe this development has been welcomed. I am not aware of any systematic negative reactions, although naturally there have been disagreements. Much of this stems from the fact that Muslim scholars have often challenged established theories that were once dominant in the field. For instance, John Wansbrough, who was active in London in the 1990s, advanced a theory of Qurʾānic studies that argued the Qurʾān was compiled much later than the traditional Muslim view holds. These ideas have been questioned and critiqued by Muslim scholars. Similarly, Fazlur Rahman, already in the 1980s, challenged several of Joseph Schacht’s foundational ideas in Islamic legal studies. Today, Muslim scholars are increasingly writing on diverse aspects of Islam and, importantly, are also questioning long-standing assumptions. In my view, this trend has been highly positive for the field.

Question 2:

A master’s student of Islamic studies (specializing in Islamic mysticism) asked the following: For pursuing this field at the PhD level in Western universities, what are the best institutions and professors? Which region—Europe, the United States, or Canada—offers better opportunities? Should I prioritize a high-ranking university like Oxford, or is it preferable to focus on a particular professor, even if they are not at a top-ranked institution? Finally, if no specific program in Islamic mysticism exists, what academic path should I follow in Western universities?

Answer:

Assuming the student already holds a master’s degree in Islamic studies, my first advice would be not to limit oneself to a single institution: never put all your eggs in one basket. Apply widely, across different countries and programs, to increase your chances of securing a place and then decide among the offers.

In terms of regions, both North America and Europe offer excellent opportunities. Europe may be administratively easier because PhD students are not required to complete coursework and can begin writing their dissertations once their proposals are accepted. North America, by contrast, typically requires two years of coursework and comprehensive examinations, which may initially seem burdensome but ultimately provide a stronger methodological foundation and a broader teaching profile.

As for institutions: in the United States, universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Berkeley have strong programs in Islamic studies. Other universities, including the University of Miami, also have reputable faculty in this field. In Canada, leading institutions include McMaster University (where I teach), as well as the Universities of Alberta, British Columbia, and Montreal. McGill University and Concordia University (with Professor Linda Clarke, though she may now be retired) are also noteworthy.

In Europe, excellent programs are offered at Exeter, Edinburgh, Birmingham, and SOAS in London, among others. Professors such as Andrew Newman (long associated with Edinburgh) have contributed significantly to the field.

Regarding the choice between a prestigious university and a good supervisor: in the long run, working with a dedicated and supportive professor is often more valuable than simply attending a high-ranking institution. If a specific program in Islamic mysticism does not exist, students may pursue broader tracks in Islamic studies, religious studies, or comparative mysticism, tailoring their research toward Sufism or related fields.

Question 3:

You mentioned the epistemological approach as one of the new developments in Islamic studies. Some scholars argue that even when one attempts to bracket personal beliefs, the perspective of the researcher—whether Christian, Muslim, or Jewish—inevitably influences interpretation. Given this, and considering that since 2000 more Muslim scholars have entered the field, some may argue that criticisms of Islam or Shīʿa denominations by Muslim scholars could have more negative consequences than similar critiques by non-Muslim scholars. For example, debates around the existence and birth of Imām Mahdī may be perceived differently depending on who discusses them. In your view, has the presence of Muslim and Shīʿa scholars in Islamic studies ultimately benefited Muslim academic communities and societies?

Answer:

My view is that a belief remains a belief, and critique of it—whether by a Muslim or non-Muslim scholar—should not be treated differently. For instance, discussions about Imām Mahdī, Wilāyat, or Ghadīr Khumm can be debated by Shīʿa scholars, and disagreement is always legitimate. The key point is not the identity of the scholar but the content and correctness of the argument. If something is inaccurate, it can be refuted through scholarly discussion.

We observe frequent disagreements among Muslim scholars themselves, which demonstrates the strength of academic debate. For example, I authored Shiʿism Revisited, and I expect some Ulama may disagree with aspects of my arguments. The important aspect is the opportunity to engage, refute, and discuss claims regardless of the scholar’s background. Forums such as Islam at AAR—an online discussion platform including 800–900 Muslim and non-Muslim scholars—provide a space for such dialogue on topics ranging from al-Muwaṭṭaʾ by Mālik to the observance of Muharram in various communities.

Question 4:

Could you clarify how funding sources influence research topics and methodological choices in Islamic studies departments? For example, governmental versus private funding, such as the Amir of Sharjah or a proposal to Ayatollah Sistani, may have different effects on faculty teaching and research.

Answer:

There are two types of funding to consider. First, endowments for professorial chairs: for example, the Amir of Sharjah donated funds to establish a chair at McMaster University. Once established, the position remains permanently; only the professor occupying it changes over time. This type of funding generally does not dictate research content or methodology.

The second type is funding for students or researchers. At McMaster, graduate students often receive tuition coverage and limited support for up to six years for master’s and PhD studies. Funding availability varies across institutions and countries. For example, the U.S. generally provides more opportunities, while some countries have stricter limits. Prospective students should explore different universities and inquire about funding possibilities, as each institution has distinct programs and levels of support.

Question 5:

You emphasized that Islam should be introduced subjectively rather than objectively. While historically accurate in the Western context, this perspective stems from the modern Western philosophical shift from epistemological realism to subjectivism. If one does not accept this philosophical turn, why should Islam’s study adopt a subjective approach? Shouldn’t the philosophical assumptions of Western scholarship be challenged first, rather than adapting to them?

Answer:

I think there may be a misunderstanding. While subjectivity is inevitable, scholarship must also be objective. Our approach is neither confessional nor apologetic. Muslim scholars in the field are not bound by Western methods or assumptions; rather, they are well-positioned to identify and correct inaccuracies in both Muslim and non-Muslim scholarship.

For example, I once reviewed a book on Shiʿism in which the author claimed that Shīʿa Muslims in a particular village in India refrained from bathing during the first ten days of Muharram—a clearly erroneous statement. While it may reflect the practices of a specific local community, it does not represent Shīʿa practice as a whole. This demonstrates why Muslim scholars’ presence in the field is essential: to correct misconceptions, provide accurate representation, and maintain scholarly rigor.

Question 6:

It seems that Western academia primarily pays attention to Muslim and Shīʿa scholars living in the West, and not those residing in the East, including Iran. Is this a shortcoming of Western academia, or is it also a limitation on the part of Muslim scholars who do not live in the West?

Answer:

Part of the issue lies in language and access. Much of the scholarship produced in Iran is not accessible or even known to the West due to linguistic barriers. While some figures, such as Ayatollah Sistani, are somewhat recognized, their full works remain largely unread in Western academic circles. For instance, it was only after Professor Sachedina translated Ayatollah Khūʾī’s al-Bayān that Western scholars truly engaged with his writings. Similarly, the works of scholars like Ṭabrisī are minimally studied in the West. This illustrates a dual challenge: Western academia needs greater exposure to Eastern scholars, and Muslim scholars must actively introduce and contextualize these works to a global audience.

Question 7:

You mentioned your proposal to some Shīʿa scholars regarding the establishment of an academic chair. What was their reaction at the time, and do you think there is still room to implement a similar project today?

Answer:

Initially, the proposal was well-received, but there were conditions expressed, such as ensuring alignment with their religious views, which cannot always be fully applied in an academic setting. I consulted with multiple scholars, all of whom supported the idea in principle. Practical implementation depends on funding and conditions that safeguard proper scholarly oversight. Overall, it remains feasible: universities welcome funding and are open to establishing such chairs, provided the financial and administrative requirements are met. Current geopolitical contexts may affect feasibility in certain regions, such as the United States under particular administrations, but other countries remain receptive.

Question 8:

How do you predict the future of Islamic studies in Western universities over the next 25 years? Do you foresee significant changes?

Answer:

Islamic studies have become an established and increasingly valued academic field in Western universities. However, its future largely depends on strategic investment in scholars, endowed chairs, and institutional support. While well-funded students from countries such as Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Malaysia are already contributing significantly, greater engagement from Iranian students is needed. One promising approach is the temporary placement of Western-based Shīʿa or other scholars in universities in Eastern countries, such as Iran or Iraq, to provide access to advanced courses and research methodologies. This reciprocal strategy can expand access to knowledge and help ensure the sustained quality and continuity of Islamic studies training.

Question 9:

A more practical question concerns the perception of applicants from Iran. Some students believe that submitting applications from Iran is a disadvantage, reducing their chances of acceptance, while others argue that coming from a ḥawzah could be an advantage. How accurate is this perception?

Answer:

In my experience, we do not discriminate based on nationality or ethnicity; applications are assessed on merit. Factors such as academic background, previous degrees, and mentorship are more important. In some cases, Iranian applicants with strong scholarly training, including ḥawzah education, may be given preference due to their solid foundation in Islamic studies. Political issues, such as visa restrictions, can pose practical challenges, but the key consideration remains the applicant’s academic preparation. While ḥawzah studies alone do not guarantee acceptance, when combined with formal academic credentials, they constitute a significant advantage.